Jackson Snell lived for his morning coffee, his routine, his ritual. Growing up on a truck farm with his parents, younger brother, and sisters in rural Alabama, he cultivated this penchant for morning coffee. It traveled with him to Chicago, some forty years ago. At sixty-seven years of age, it stayed with him. This daily routine fortified his resolve that his decision to accept a transfer forty years ago was the right one.

Now he lived in East Lake View, not a swanky neighborhood, but lovely nonetheless. As he walked through the doors of his neighborhood coffee shop, a warm greeting waited as it did every morning.

“Hey, Jackson, how are you this morning?” asked the young barista.

“Jest fine, Mindy, jest fine. How ‘bout y’all?”

“Can’t complain. The usual?”

“Sho’ ‘nuff. Like they say, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. But maybe this once get me one of them lemon squares today.”

“You got it.”

After paying for his coffee with a generous tip, he settled into his favorite window seat. The morning traffic on Clark Street punctuated a smile across his face.

He settled into city life with such ease it surprised him; he made friends and grew to love it. It took a while, but he managed to even switch his allegiance from the Braves to the White Sox and didn’t find the designated hitter rule the evil he always thought it to be.

His smile broadened as his mind drifted back to those hard scrabble days on the farm. It wasn’t a longing for the good old days, but it was for the change his life had taken. Like they say, ‘Life is good’.

Retired now, he found his life a lot more than good — morning coffee and this afternoon at the zoo with his grandkids. What could be better? Life was damn good, he thought.

While he sat contemplating his life and how good he had it, he didn’t notice the attractive, matronly woman enter the shop, go to the counter and order tea. Jackson paid no attention to her, until she sat at his table directly across from him.

A quick glance around the shop revealed a half dozen empty tables, but here she sat right opposite him at his window table. She placed her purse to her left, grasped her tea in both hands, and took a deep sip, closing her eyes to enjoy the warmth drifting down her throat.

Looking up, Jackson saw an attractive older Black woman, not as old as himself, but north of fifty. Soft, hazel eyes, no make-up, a pale-yellow blouse with no jewelry completed the picture. Her smile beamed, yet it seemed shallow and forced.

“I’m sorry, ma’am, but do I know you?”

“That truly saddens me, Mr. Snell. Of all the folks that done crossed yo’ path, surely, I thought you’d remember me; Viola McBee.”

“I’m sorry, ma’am, but I have no recollection of that name, or such a lovely face.”

“Well, maybe this will jog ya’ll’s memory some.” As she reached into her purse, Jackson took a sip of his coffee. When he looked back up, Viola McBee dead aimed her small .25 automatic at his face.

She pulled the trigger twice. The impact of the shots threw Jackson out of his seat and onto the floor. Viola McBee nestled her gun onto the table and resumed her tea.

Two hours later she sat in an interview room at the thirteenth precinct. Her hands folded demurely on the table in front of her, her expression calm and unruffled, at peace. As the detectives watched her, the only items that seemed to be missing were white gloves, a pillbox hat, and a bible.

Detectives Frank Lintelli and Martha Stanton observed for a while. Viola said little more than to confirm her name and address.

“I don’t get it. Mr. Snell was overheard telling you that he didn’t know you, yet you shot him to death. I don’t get it.”

“Mr. Snell misspoke. He knew me, he just didn’t remember me.”

“I still don’t get it,” said Stanton. “Did you know he was planning to take his grandkids to the zoo later on today? What if they were there?”

This seemed to jolt her back to the present. She stared at the interrogators. “I would have waited. He had grandchildren?”

“Yes, but thanks to you, they don’t have a grandfather anymore.”

“It would seem so, but they didn’t need this one. No, not this one.”

“The family will never be the same. Never.”

“Happens to the best of families, don’t it? Look, I done what I done and ain’t gon’ apologize for it neither.”

“We’re beginning to get that, but the question still remains: why did you do it?”

When the words were out of the detectives’ lips, Viola’s eyes averted theirs, tears formed in hers, the hazel color shrouded with moisture. She reached into her blouse and brought out a small, unsealed envelope and plopped it on the table.

“This be my answer to your ‘why’.”

Martha Stanton handled the envelope as if picking up a double-edged razor; she gingerly opened it. Inside she found a folded, yellowed newspaper clipping — a small article and picture. “Oh, my God!” she exclaimed. Lintelli reached over and took it from her hand.

“Jesus!” he said.

The article was an explanation of the picture. It was a lynching in Coffee County, Alabama, August 1968; White people standing around; men, women, children as if at a Fourth of July picnic. Drinking from cups and bottles, smiling, eating snow cones. No caption, no explanation under the photo, just two figures circled.

A black man hung from a tree; his neck elongated, his tongue purpled and swollen, bulging out his mouth, his pants pulled down around his ankles, the lower half of his body drenched in blood.

“They done hung my Daddy. That be August 1968. Them circled pictures be Mr. Jackson Snell and his buddy, Caleb Potter.”

“They lynched your father?”

“Yes, suh, they surely did.”

“Why?”

She threw both detectives a glance that revealed to them how stupid their question was.

“’Cause it was 1968, Coffee County, Alabama. Cain’t you read? That’s all the reason they needed, but they did have another.”

Lintelli glanced once again at the photo. “Why just kill Mr. Snell? I mean it looks like there were a lot of participants here.”

“Maybe ‘cause everybody there didn’t rape my Daddy’s eleven-year-old daughter, his only daughter; only Jackson Snell and Caleb Potter.”

Viola’s bottom lip quivered; the tears poured out now. “They raped me. They yanked me off the road. I was comin’ home from the store. They took me back in the swamp and took turns.

“When they had they fill, they let me go, tellin’ me they’d be back when I got older and learnt some things ‘cause they loved them some dark meat. I can still hear them laughin’ as they drove off.”

“I tol’ my Daddy and his mistake was he went and tol’ the sheriff. That sheriff went and tol’ them dirt farmer Snells. Next thing I know is they breakin’ in our house and draggin’ my Daddy out.”

“As they was draggin’ my Daddy out, my Mama held me back. I was cryin’, screamin’, and beggin’ them not to. That’s when Mr. Jackson Snell turned, smiled, and winked at me. That’s also when I knew this day would come.”

She lowered her head, gazing at her lap, then slowly raised it to face the detectives. “So, you say, Mr. Snell had grandkids? Well, I ain’t got none. Aftuh they done what they did, I couldn’t have no kids. No kids fo’ me meant no man evuh looked my way. It was like I was marked since I been eleven. Yes, suh, marked. No man wanted me, but they was no man I wanted aftuh they done, what they did.”

Both Lintelli and Stanton sat there, stunned as if hit by lightning, not knowing what to do or say. After a somber silence, Stanton spoke. “Ms. McBee, I don’t know what to say. I… “

“Don’t fret about it none, sweetheart. I knew what I was doin’ and I knew what the outcome would be, so it ain’t yo’ problem. It’s between me and the Lawd. Hope She will understand.”

“She?”

“One of my last remainin’ hopes fo’ forgiveness.”

As if on cue two uniforms came in to escort Viola McBee away and back to the holding cells. She turned one last time before exiting through the door.

“You might wanna call the Coffee County Sheriff’s Office and clear up a missing person’s report for them. They can find Caleb Potter’s body down by Bryson Creek. That’s where they took me that day.”

“Also tell them they woulda been another, but the devil came up and snatched that sheriff befo’ I could.”

As she left out the door, the detectives sat, each in their own way, trying to define justice and its true meaning.

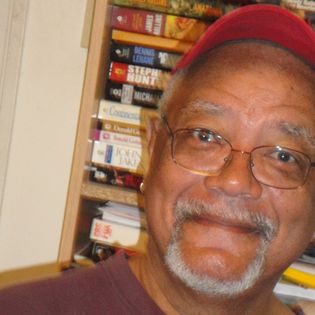

Arnold Edwards is an author, retired teacher, and coach. He graduated from Quigley South Seminary in Chicago. He holds a BA in history from Southern Illinois University. He has sold eight short stories and is currently working on three novels. He has authored two full-length screenplays and several teleplays, a few of which were for now-canceled shows and three in search of a series. His published stories appear in Black Lace Magazine, Cricket, YAWP Magazine, Downstate Story, Gemini Magazine, Frontier Tales, and Mystery Tribune.