Growing up in the Motor City (aka Motown) during the sixties, I was a politically precocious child. My parents had been Black members of the Communist Party when they lived in Greenwich Village, a decade before moving to Detroit. McCarthyism had been at its height, and Americans, Black and white, suspected of being pro-Communist were publicly rebuked, blacklisted, jailed, and, sometimes, had their passports revoked. The country frenetically searched for Communists under beds and behind closed doors. I can only imagine that the raging anti-communist sentiment of that era contributed to my parents’ decision to remain close-mouthed about their political beliefs, even to their own children. Fortunately, two Negro graduates from the University of Michigan, my father from the medical school and my mother from the school of nursing, who both hailed from unassuming southern families, were not high on McCarthy’s radar. And although they never shared their political history with me or my siblings, the books they made accessible to us, the television programs we could and could not watch, and their discourse about the Civil Rights movement and of Black historical events, all helped shape my worldview. My father established a large medical practice in Detroit, where a majority of the Black populace had migrated from the South and where the labor union movement was robust. He exposed us to values and practices he hoped would give us a head start in a society he knew did not nurture Negroes.

As soon as I was old enough to hold up a sign, my mother drafted me to accompany her to labor union rallies and civil and human rights marches where we protested nuclear bomb testing, demanded an end to the Cold War, urged the legalization of abortion, and called for freedom for all political prisoners.

Each time we attend a march,

she clasps my hands around the wooden handle

to demonstrate how I should hold my sign

as we join fellow protesters . . .

My mother is a patient teacher in the art of protest

and explains the how’s and whys of saying “no”

to the Establishment, her word, not mine.

Among my childhood friends, mine was the only mother who was a self-proclaimed existentialist and whose bookshelves contained authors such as Simone de Beauvoir, Camus, Sartre, and Bertrand Russell. I do not recall seeing bookshelves in most of my friends’ homes. My mother also made clear her intentions to visit every socialist and/or communist country on the globe.

One of the most interesting aspects of my mother’s parenting style, is that she did not simply read existentialist philosophical theory, she embodied it. When I left home to attend Stanford University for undergraduate education, she said, “If I don’t hear from you, I will assume that everything is alright.” That became her mantra. While my freshman classmates were fielding calls from their parents who were anxious for an update about classes, or adjustment issues, or grades, my phone was silent. My mother believed in the singular freedom of the individual to grow and follow his or her own path. When she accompanied my brother, Paul, to Yale College for the start of his freshman year, she kissed and hugged him at the quadrangle gates and then walked past other students’ mothers carrying supplies to decorate their darlings’ dorm rooms.

The ideologies of my parents were best reflected in the music they played in our home. During weekday dinners or on weekends, their vinyl records filled the house with a rich mixture of folk protest songs, prison work songs, Negro spirituals, and classical music. My mother’s record collection included Odetta, Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, the Weavers, and Harry Belafonte, along with a smattering of blues singers. My dad was a classical music aficionado. He also shared with my mother a fondness for Paul Robeson’s deep tenor and his unrelentingly passionate songs highlighting the plight of the oppressed. It made sense that their firstborn boy, my first sibling, was named Paul, in honor of Mr. Robeson. Paul Robeson was blacklisted on charges of un-American activities during the 1950s. I knew that story inside and out, like some children knew the story of Hansel and Gretel. I had a vague awareness that my parents were oddities compared to my friends’ parents and that our household was not your typical Negro household.

Immersion in books was my solace, my joy, and my retribution, even when I could not comprehend all what I read. My parents had a large library to which I was given free range. No book in the room escaped my perusal. They possessed a bound copy of the petition presented to the United Nations in 1951 entitled We Charge Genocide. The book was compiled by William L. Patterson of the Civil Rights Congress and charged the United States government with genocide against Negro Americans. Page after page of this document contained black and white photographs of Black men hanging awkwardly from trees, each with a synopsis detailing the circumstances that resulted in their murder.

Curled up on a plush sofa in our family room with the book in my lap, I peered at the photos, pondering them with morbid fascination. I traced the dark figure with my finger and tried to imagine the scene. What did this man feel when the crowd held him down? Did the smells–of chewing tobacco, putrid sweat—make him recoil? Did the crowd jeer or was there anticipatory silence as they slung the rope tight around his neck? Did he flail and kick in anger until some rednecks beat him into submission? Or did icy fear prevent any resistance on his part? In those last seconds before his neck snap-popped, did he ask himself or his God, “Why me?” I asked this question for him and for each person pictured on those pages: Why? Who would do such a thing as string another human being to a tree by his neck?

Who does this? It’s a rhetorical question,

because I see the white people gathered around the trees, watching.

Why would anyone even consider burning a person alive? What type of society was this that condoned atrocities such as cutting off a man’s penis and stuffing it in his mouth? Yet, these narratives were about real people whose lives ended in horrific and grotesque ways because of their skin color. The revulsion and the disquietude that I experienced after reading the book resonated deep within me.

After reading, We Charge Genocide, something within me snapped. I felt as though I was standing on the bank of an island watching as the rest of the country drifted further off into the distance. I felt disenfranchised, disembodied, and, disconnected from the concept of being American. I no longer wanted to have anything to do with this country or the things that America stood for. This was my first experience of feeling like an outsider in my own country and the point at which I pledged to someday become a native expatriate.

Around this time, I began writing poetry and titled my small collection of poems, Poems of Black Pessimism. I wrote in reaction to sociopolitical events and my poems were deeply introspective. At fourteen, I grappled with the question of what it meant to be a Black person in America. The Detroit Free Press, a local newspaper, ran a poetry contest around the same time and my poems were front and center:

The French are home in France

Spaniards retreat to Spain

I looked in vain for Negro-land, But

The whereabouts of the country escaped me

Perhaps it has been drained for lack of popularity.

Not long thereafter, I was contacted by Dudley Randall, the then-editor of Broadside Press, a Black literary press based in Detroit. He expressed interest in seeing more of my work and I made a slow motion note of his request. I say slow motion because giving him a copy of my poems meant my having to retype each one of them. Computers did not yet exist. Circumstances would prevent me from executing my plan. Some fifty-plus years later, I marvel that my poetry is being published by the same press.

My father disavowed formal membership in organizations that embraced class distinctions within our Black community, although, such groups were popular. I attended public schools, from elementary through high school. My brothers and sister attended private Quaker schools. We were forbidden to participate in Detroit’s elite Jack and Jill social club. We were shipped off to private summer camps but could not attend Cotillion balls—another hallmark of Black high society. My parents frowned upon membership in Black fraternities and sororities. As a result, I didn’t grow up yearning for the social trappings of Black society. That is not to say that I was not comfortable with material trappings. I was. But I harbored a modicum of outrage that racial, class, and economic disparities needed to exist. From my oversimplified perspective, there was enough wealth to go around such that everyone could be provided the basics.

It was the mid-sixties, and the tumult of the Civil Rights struggle was front and center in the news.

On black and white TV, Civil Rights marches chokehold the news.

Aunties are composed, in shirtwaist dresses and tiny-heeled pumps.

Uncles stand proud, in suits, white shirts, and ties. They’re dressed to vote.

They try to be brave as German Shepherds chomp at their ankles.

Fire hoses squelch their will. Dying to vote. They are dying to vote.

Other competing news items included the Vietnam War, Malcolm X’s death, the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, and the emergence of the Black Panther Party.

I initially joined the Young Socialist Alliance, an organization at my high school. The group was comprised of white teenagers whose political idealism surpassed my own. Then I enlisted in the Black Panther Party at the age of fifteen. The group was not sponsored by my high school. I was attracted to the fact that these were young Black people, knowledgeable of our history and oppressed status, who were taking matters into their hands and pushing back at the system.

they render the revolution

an enticing taboo and brandish big guns–

these black activists–shaking, moving,

molding history with their hands

I wish I could say that my political activities were supported by my parents, particularly, given their own historical political involvement. Quite the opposite. My father’s reaction was so extreme as to haunt me for many years to come. It was one of the reasons I invested in therapy as soon as I began working and could afford it. When I began writing, after many years, it was the one thing I dared not write about. Why? Too triggering.

Of course, when I began my MFA program, my first professor, Kwame Dawes, said, “You should write about that which you are afraid to write.” He inspired me to take the plunge, peel back the time, and enter the era of my teenage participation with the Detroit Black Panther Party. Initially, I was scared to reminisce. I was terrified to touch the wound. But I began writing, little by little. I am still unsure whether I will share the work with the elders in my family who are alive. The jury is still out on that issue. Some of my elders insist that their memories of what transpired in the 1960s are different than mine.

In my very first poem about the Black Panthers, I evoked the image of myself hailing a Black cat like a cab and climbing on.

I hailed that Cat

like a gypsy cab

threw my leg

over its wild part

and clutched its warm recesses

I rode with revolutionary wile

into the city’s bowels

then rose up through its consciousness

flying high like Icarus

It did not then occur to me to employ the myth of Icarus, either in the title or as a recurrent theme throughout the collection. It took my attendance at a lecture on mythology by Mahtem Shiffraw in which she emphasized the importance of creating echoes employing myth to provide cohesion in a body of work.

Initially, I thought of titles such as Running with the Panthers. The manuscript was a coming-of-age narrative, and I envisioned myself hanging out with the Panthers, in the vernacular sense. As the collection grew and I began to weave in the poetic connection with Icarus, it became clear to me that, as much as this was my story, it was really about the rise and fall of the Black Panther Party. Fall as in the literal sense. The title declared itself: How the Black Panthers Fell from the Sky. The explicitness of the title allowed me to situate my personal story within the larger framework of the Black Panther Party’s decimation by the federal government. It also gave me room to create speculative narratives as to why the Black Panther Party was destroyed.

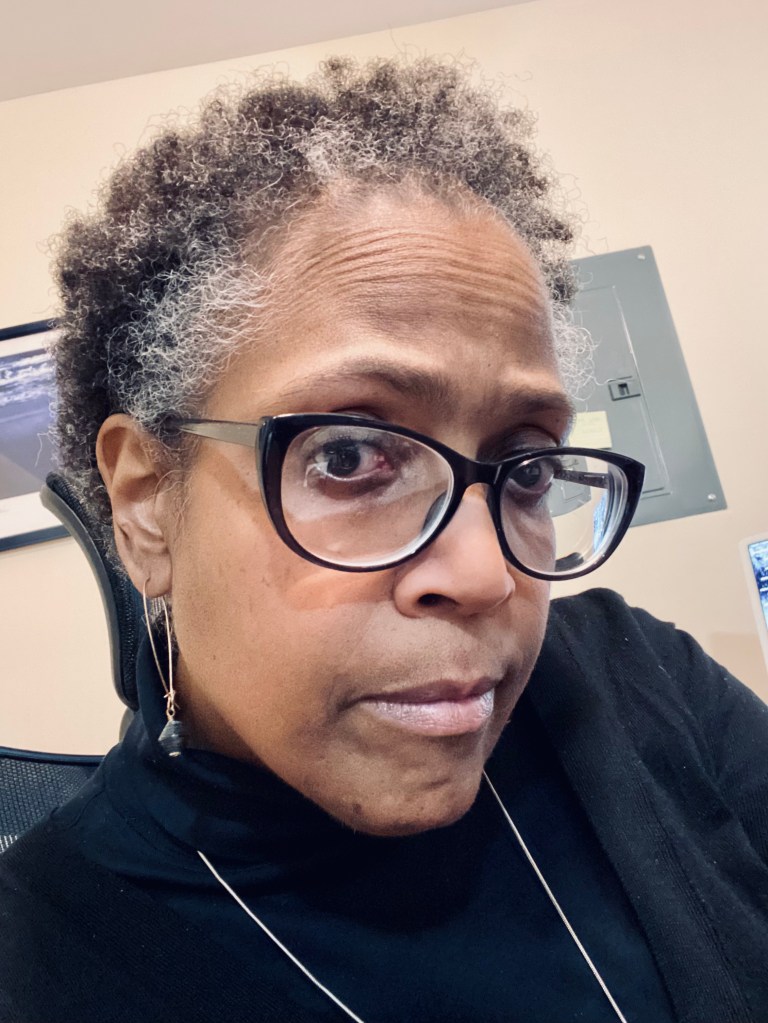

Joanne Godley is a thrice-nominated Pushcart and Best of the Net poet and writer, and a recent MFA graduate from Pacific University. Godley’s work has appeared or is forthcomingin Crab Orchard Review, The Kenyon Review Online, and The Massachusetts Review, among others. She is an Anaphora Arts Fellow in poetry and fiction. How the Black Panthers Fell From the Sky, is a memoir-in-verse and Godley’s first poetry collection. It won the Naomi Long Madgett award for 2025 and will be published in 2026. You can find her at Joannegodley.com, on Instagram at @indigonerd, and on Bluesky at jgodley-doctorpoet.bsky.social