FROM THE HOUSE OF COMMONS

5/24/1847

We must acknowledge the Irish are dense,

superstitious; count on God for magic

interventions: pots of gold, good crops,

rents forgiven. One must admit it’s tragic,

them shuffling to the work-house,

with their pack of little monkeys, clinging.

We’re the ones deprived of maids, drivers;

we knew the Irish lack ambition; they can’t

even stay alive.

ELLEN O’CONNOR A BABY DYING

12/3/ 1848

You will always be my babe, my sweet.

I did not see us dying on the same day

in the rain and starving, cold; I did try

to keep you clothed and fed, there was

no way to find sustenance. Or warmth.

I know God will soon visit us, take us

to a place of eternal rest, vast food.

It’s not hard to go; I shall hold you, kiss

your pale face.

FROM THE CORK EXAMINER,

BY JERIMIAH O’CALLAGAN

DAMNING THE GUARDIANS

6/16/ 1847

How dare they call themselves guardians;

men who deny clean water to the poor.

They should see hundreds of the decomposed,

then be forced to say their names; and to pray

they never see their own dead children laid

next to rotting paupers, in the jaws of dogs

and rats. And their ample wives afraid to starve,

tossed in a ditch with the unloved.

ENDLESS BURIALS

2/2/1847

More deaths, less relief; the dearth of coffins

and plots have shaken me to the core. Some are

of the belief trap coffins give dignity

to the dead. A hinged box, stuffed with two

or three deceased, is brought to a pit, and bodies

are fed into the earth; then re-used to increase efficient

burial. Poor lads can build only so many each day,

they are weak and scarcely fed.

A FATHER’S CHOICE

1847

A cat has little meat on it; when one is mad from hunger,

anything will do. The father’s choice is brutal. Eat nothing

or eat the poisoned cat. They knew the cruel lord’s men

would soon be at the door to throw them out. It would

have been human to dig them graves in the seized field,

what more could they ask for: a place for their remains.

WARNING

11/15/1847

They are right, the farmers; they hear the fields’

bleating, feel decay with their own hands, cracked

and calloused, the smell of rot. They know yields

are nil, the starving season has them backed against

the wall. They’ve all been driven to madness.

Food grown by the famished is laid waste or pilfered,

shipped to the English who never miss meals.

OUTRAGE

1/1/1848

The widow cannot speak, is always at the mercy

of such men who unearth small growings from her

sparse plot, quite aware that she and five children

will die in cold fall. She watches them dig raw

potatoes out of her patch; praying it would yield

something this time. Who loosed these thugs,

marauding louts, on paupers who have little to nothing.

A CONCERNED READER WRITES

2/5/1849

His days were spent starving; his life was deemed

extinct, a miserable creature. His fate was sealed,

being Irish. Pat’s Ma had dreamed her boy would

be safe and fed; not a plate of nettles for his last meal.

He was sawed open by the coroner: who would eat

what sheep eat? This man, a bag of bones clawed

at dirt to loosen roots, having no meat.

A READER DESPISES THE QUEEN

10/26/ 1850

The Famine Queen is so pleased to eat our food, tons

and tons of meat and butter; the Monarch’s

not keen to see our cankered fields, the skin

and bones our children are. We are not her

kind, no fancy tea at four, we do not eat scones;

or anything, having nothing to grow.

HONORA’S MIDDLE DAUGHTER, LIZZIE

2/5/1849

Where do we go, our Ma dropping dead right

in front of me eyes? She’s not a wretch or creature,

she’s been a good mother. It might be a crime

to hunt turnips, it’s food for us, not jewels

or cattle, she would never steal from the rich,

just root vegetables. How do we live

without our Ma? Don’t ever split us; we’re one,

not three, she made a vow.

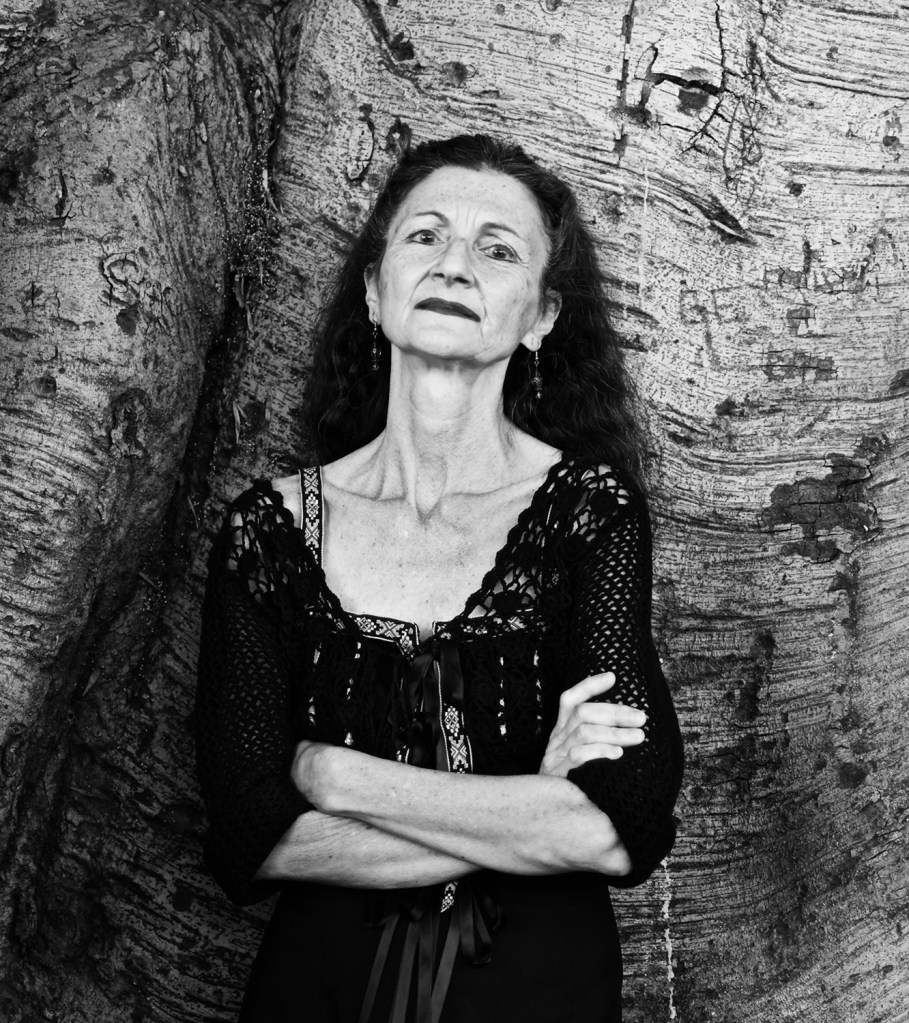

Catherine Harnett is is poet and fiction author. She has published three books of poetry, and her work appears in numerous magazines and anthologies. Sheretired from the federal government and currently lives in Virginia with her daughter. Her short fiction has been published by the Hudson Review and a number of other magazines, including upstreet, the Wisconsin Review, Assisi and Storyscape. Her story, “Her Gorgeous Grief,” was chosen for inclusion in Writes of Passage: Coming-of-Age Stories and Memoirs from The Hudson Review, and was nominated for a Pushcart. She can be found at catherineharnett.com